This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Why the dental care timebomb may provide an opportunity for reform

October 08, 2020The scale of the problem

The pandemic has caused issues in every part of health and care, but the problems in dental care appear particularly acute. Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, these problems were already mounting. Statistics released from Public Health England revealed that almost a quarter of five year olds in the UK are experiencing tooth decay, and furthermore that it remains the number one reason for hospital admission in five to nine year olds.

There is also a concerning divide in dental health standards between the north and the south, and rich and poor. A report by the Nuffield Trust highlighted that people from less affluent backgrounds are twice as likely to be admitted to hospital in need of urgent dental work than those who are better off. Specifically, 14% of people from deprived backgrounds have been hospitalised in this capacity, against 6% of the better off. Oral health shouldn’t be a postcode lottery.

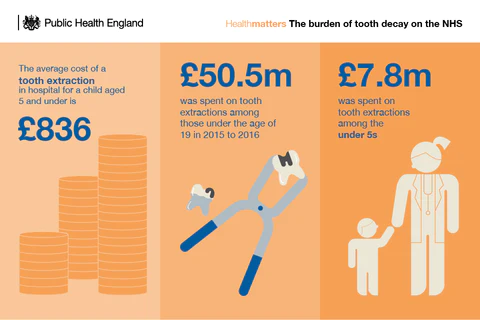

In turn, this places significant pressure on the NHS. In 2014, all NHS dental treatment costs were £3.4 billion with an estimated additional £2.3 billion in the private sector. In the financial year 2015 to 2016, the cost of tooth extractions was approximately £50.5 million among children aged 0 to 19 years. This was for tooth extractions for any reason however the majority of extractions were for tooth decay. Among children under 5 years of age there were 9,306 admissions for tooth extractions (with 7,926 specifically identified as being due to tooth decay), at a cost of approximately £7.8 million. Dental decay is entirely preventable, however it remains a chronic problem not only within the UK but also worldwide, and one that risks being stretched to breaking point in the current environment.

The teeth of a crisis

The pandemic has caused a backlog of 15 million appointments, leaving many patients with existing problems suffering greatly, and The Guardian reports that dentists are fearing a ‘tsunami’ of of post lockdown tooth decay. Practices have re-opened since initial lockdowns earlier this year, but in a capacity that makes it impossible for them to meet current demand. Strict infection control measures imposed by Public Health England mean that many practices can see only a few patients a day, whereas before they would have seen 30 +. Dentists in England must follow a ‘fallow’ period of 60 minutes after any procedures that generate aerosol particles, such as using a drill. It means that they can see far fewer patients, and also places significant stress on the fundamentals of their business model. Eddie Crouch, chairman of The British Dental Association, which represents 22,000 dentists in the UK, states that thousands of clinics are struggling to stay afloat, and if practices fail patients will have “nowhere to go.”

Andrew Gregory reports in the Sunday Times that “NHS data indicates that 83,800 treatments took place in May, compared with a usual monthly average of 3.3 million”, going on to specify that in August dentists delivered only 811,029 courses of treatment, less than a quarter of the number typically carried out. Many dentists worry that this backlog is going to go on for years, which — when coupled with problems that existed before the pandemic, and breakdowns in basic oral care routine — place the UK’s long term future oral health at serious risk. The time spent to clear the list of patients waiting to be seen is significant with current restrictions, and any further suspension of services during the second wave could cripple dentists and generate consequences that are simply insurmountable.

The value of a healthy smile and the opportunity for reform

The difficult period that we face as a nation has emphasised the vitality of a healthy smile. Whilst we cannot hug or shake hands with others, a smile becomes our primary tool for connecting with others and displaying essential human emotion. As the pandemic continues to have devastating health, economic, and psychological effects, it is perhaps more important than ever.

Many dental services have re-opened since June and are operating tentatively under the guidelines imposed by PHE. Rather than seeking to eventually resume normal service, perhaps the crisis offers an opportunity for reform, and a chance to rethink the future of dentistry whilst addressing systemic failures such as child tooth decay and the postcode lottery. Throughout the pandemic, dental personnel across the world have been redeployed in front-line services to provide a range of clinical procedures way beyond their usual scope of practice. The scale and pace of this integration into the wider health system is unprecedented; dentists, hygienists, and nurses have all played a significant role in supporting health services deliver covid-related care during the crisis. In the process, they have developed new skills and knowledge.

Rather than being siloed from mainstream health care, the pandemic has clearly shown that dental personnel can be successfully implemented into the wider health system. Why not delegate the clinical roles of dentists into a fully integrated model of care? The current restrictions on aerosol generating procedures for example, represent an opportunity to re-calibrate dental care towards a less invasive, and more preventative approach, one in which dental teams work together to tackle the shared risk of oral diseases. Given that the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing socioeconomic inequalities, and will continue to do so in oral care, why not re-organise resources to offer a novel approach focused on widespread prevention?

Doing so will require brave decision making from politicians and dental professionals alike. But the time is ripe for change, and the time is now.

Bitesize news direct to your inbox.

Sign up for Bitesize, our monthly newsletter, for the latest dental tips, healthcare news and more, including 25% off your first box